You Were Made to Make a Difference

There’s something inside all of us that refuses to settle—something that pushes us beyond just getting by or even having a good life. Deep down, we want our lives to count. We want to invest our energy, our gifts, and our drive into something larger than ourselves… something that creates a legacy that echoes through our families, our communities, and beyond.

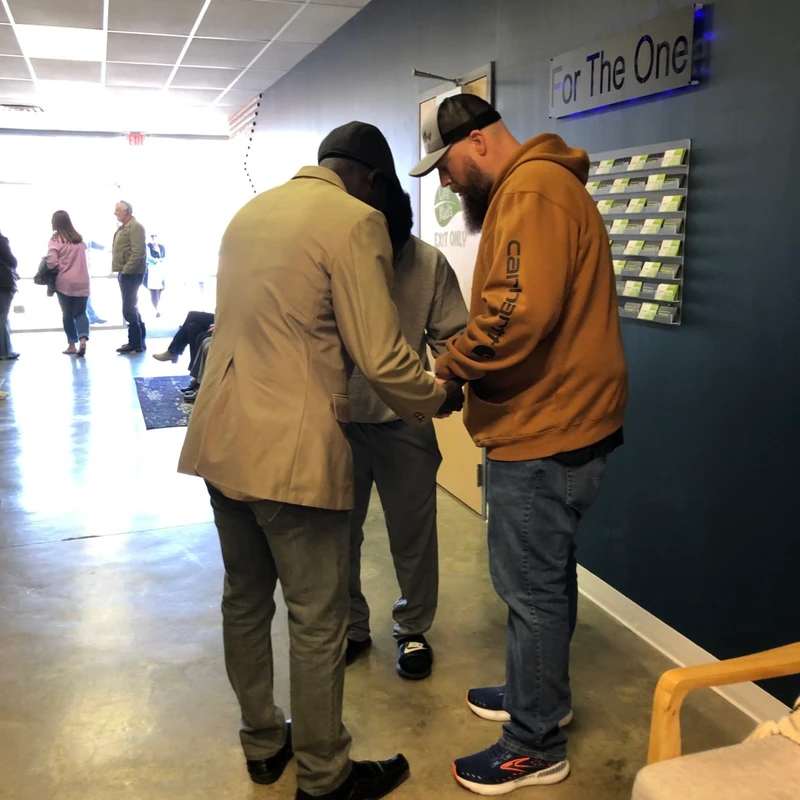

We’re here to help you recognize that calling and step into the kind of life God designed you to live—a life of purpose, impact, and eternal significance.

Join us this Sunday. Bring the whole family—our environments for kids and teens are designed to encourage, challenge, and inspire them. Come be part of something that makes a difference here, near, and far… something that matters forever.

LifeKids

Encounter

Next Steps

Current Series